Burning pigs, dogs carrying out suicide attacks, and rats clearing mines. Throughout the years, animals have often been used in all sorts of inventive ways on the battlefield.

♦ Dogs

In the First World War, swift dogs ran back and forth between units at the front with messages attached to their collars.

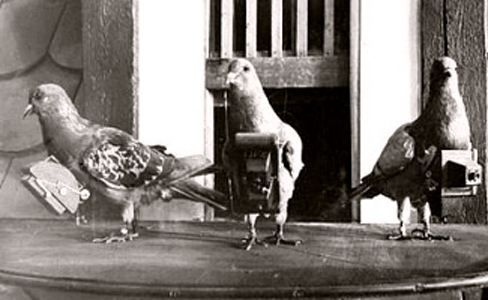

♦ Carrier pigeons

The news of Julius Caesar's victory over the Gauls in 52 BC and Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo was spread by carrier pigeons

The pigeons has been in military service for thousands of years, whereas other animals were used exprimentally.

♦ War pigs

Zo schreef de Romeinse geschiedschrijver Plinius de Oudere over oorlogsvarkens, die ingezet werden tegen de olifanten van de vijand. Ze werden overgoten met een brandbare vloeistof en aangestoken. Door hun schelle pijnkreten zouden de olifanten in paniek zijn geraakt.

In oorlog is alles geoorloofd, zelfs de gruwelijkste dingen.

♦ Monkeys

During the Chinese Song dynasty in the mid-10th century, monkeys were deployed.

They were wrapped in straw, soaked in oil, and set on fire. Once released into the enemy camp, these living fireballs caused great devastation.

♦ Handeld with respect

Although animals have endured a great deal in the many wars throughout history, four-legged or winged comrades are generally treated with respect.

There are many remarkable stories about carrier pigeons, horses, and dogs whose endurance and dedication positively influenced the outcome of wartime situations.

♦ Bucephalus

Many war animals have become famous, but Alexander the Great’s horse Bucephalus perhaps takes the crown. It carried its owner in more than 30 battles, always at the forefront.

The grateful Alexander founded a city, Bucephala, in memory of his horse.

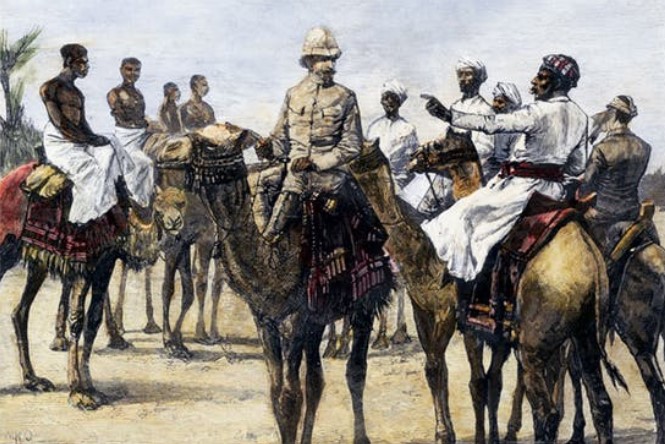

♦ Camels worked themselves to death

Camels are tough and better adapted to life in the desert than, for example, horses and mules. They can go a week without water and can close their nostrils during sandstorms. But even a camel needs care.

In 1877, Russian General Mikhail Skobelev had 12,000 healthy camels at his disposal during the Russo-Turkish War. Some time later, his army returned victorious with only one camel. The rest had succumbed to the harsh Asian climate.

Around the same time, the British were fighting in Afghanistan, where they lost 30,000 camels over a few years.

The British author Geoffrey Inchbald, who served in the British camel corps during the First World War in Egypt, described how camels died en masse because soldiers accustomed to horses used them as pack animals.

Camels often caught colds or contracted other illnesses, and if their hooves got wet, they suffered from fungal infections.

If they were not fed from buckets but had to eat off the ground, they swallowed so much sand that they often developed colic or a gastric ulcer.

Geoffrey Inchbald wrote:

‘Only God knows how much these once-beautiful animals suffered, but they protested no more than usual and endured until they succumbed to exhaustion. When we looked back at the route we had traveled, we saw an endless line of dead camels stretching into the distance.’

♦ Bats instead of an atomic bomb

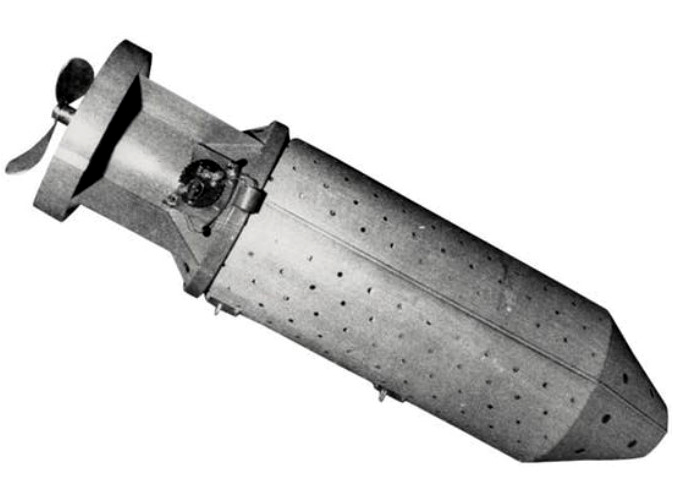

In January 1942, American dentist Lytle S. Adams approached President Roosevelt with an idea that, in his view, would force the Japanese to surrender: bat bombs.

Such a bomb consisted of 26 cages, each containing 40 bats. Each bat carried 20 to 30 grams of napalm, which could be ignited with a timer.

The bomb was to be dropped from 1,500 meters above a city and then descend further by parachute.

When the cages opened, the bats would spread over a large area.

Theoretically, ten planes could drop more than a million bats. Practically, it also seemed feasible. A swarm of test bats nested under a fuel tank at a military base, causing a massive explosion

Ultimately, however, the atomic bomb was chosen, as it could be developed more quickly.

But until his death in 1970, Lytle S. Adams maintained that his invention would have struck Japan as severely as the atomic bomb did in Hiroshima.

♦ Explosive dogs attacked a German tank

In 1941, the Soviet army tried to halt the German advance using every possible means—even anti-tank dogs.

The idea had been developed since the 1930s in military training camps. Dogs were trained to run under a tank and release a mine they carried in their mouths.

The mine was controlled remotely or by a timer so the dog could get away in time. Unfortunately, the dogs often returned to their handler with the mine still in their mouths. In a wartime situation, this risk was unacceptable.

Therefore, the mine was programmed to explode when the dog reached its target. The tank—and the dog—would then be blown up.

In practice, however, the method did not work optimally. The dogs became confused by the smell of gasoline from the German tanks. They had only been trained with Soviet tanks, which ran on diesel. No one in the training camps had considered this small but crucial difference.

It is not known how many German tanks the dogs disabled during the war, but of the first 30, only four dogs exploded near a tank

♦ Rats trained to detect mines

In 1941, the British came up with the idea of stuffing dead rats with explosives and having saboteurs place them in the coal supplies of German munitions factories.

If a rat were then shoveled into a furnace, the boiler would explode. The first shipment of rat carcasses was intercepted by the Germans, who were so alarmed that they launched a search operation for explosive rats. The British plan fell apart.

The Russians had more success when, during the siege of Stalingrad, they infected rats with rabbit fever—which causes fever, headaches, and fatigue in humans—and released them behind enemy lines. At least 50,000 Germans were infected

In Mozambique, Belgian deminers train rats to sniff out mines. In half an hour they can search an area of 100 m², much faster than humans.

♦ Carrier pigeon awarded a medal for bravery

Birds with homing instincts have been used as messengers in wars for more than 3,000 years, but the two world wars marked the peak, with 250,000 active carrier pigeons serving the Allies alone.

They were so important that in England, injuring or killing a carrier pigeon was punishable by six months in prison. Some pigeons were even awarded military honors.”

In 1946, the American carrier pigeon G.I. Joe was brought from the U.S. to England to receive a medal in the presence of several high-ranking officers.

During the fighting in Italy, G.I. Joe delivered a message in record time that a village occupied by the enemy had been recaptured.

‘We also serve,’ read the inscription on G.I. Joe’s medal.

If G.I. Joe had been just five minutes later, American bombers would have leveled the village—with 100 American soldiers inside.

♦ Elephants used as scare tactic

Elephants were forced to break through enemy lines with brute force, but injured elephants often panicked and then became extremely dangerous

Long before Christ, the Indians used elephants as weapons of war. In Europe, elephants first made military history in 218 BC, when the Carthaginian general Hannibal led his large army, including a number of war elephants, over the Alps.

Of the original 37 elephants, only a few survived the harsh journey, and they played no significant role during Hannibal’s campaign in Italy.

On the battlefield, elephants mainly instilled fear. They could easily trample infantry, but the Romans quickly learned how to deal with the beasts

When Hannibal unleashed 80 elephants on the Romans at the Battle of Zama in North Africa in 202 BC, the Romans frightened the animals with the sound of trumpets.

In panic, the elephants turned around and trampled over their own army. The Carthaginians lost the battle

Elephants were never very important in European wars, but the British army still used them in World War II in Burma to transport supplies

Source: Historia

Kasper Nielsen & Boris Koll