The sad story of a shipwreck was the inspiration for one of the masterpieces in the Louvre in Paris.

♦ What is The Raft of the Medusa? ♦

Does the painting The Raft of the Medusa in the Louvre depict a real event?

The Frenchman Théodore Géricault based his masterpiece on a real shipwreck.

In 1816, the frigate Méduse ran aground on a sandbank 60 miles off the west coast of Africa.

The disaster, which led to the deaths of 140 people on board (crew and passengers), attracted widespread attention throughout Europe due to the survivors' account, which discredited the French government by questioning both the competence of the captain on board and the organization of the rescue operation. It later became a subject for many important painters, including Géricault, who found inspiration in it for his Raft of the Medusa.

The lifeboats could hold 250 people, and 147 others climbed onto a wooden raft that was towed behind them. But the captain had the ropes cut because the raft was slowing down the lifeboats.

Fighting soon broke out on the raft over the scarce provisions. Twenty people died on the first night, some by suicide. The waves pounded the overloaded vessel, and only the shipwrecked in the middle were not washed away.

After four days, 67 men remained on the raft. Hunger drove some of them to cannibalism. The law of the jungle prevailed: the dead were eaten and the weak thrown overboard. On day 12, the French ship Argos spotted the raft.

Fifteen people were rescued, five of whom later died. The captain and the rest of the crew in the lifeboats managed to reach the French colony of Senegal.

♦ Historical background

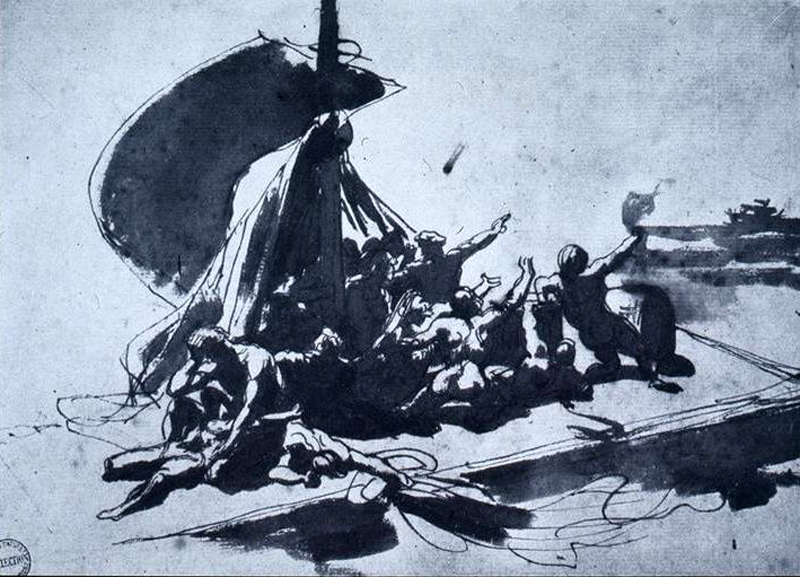

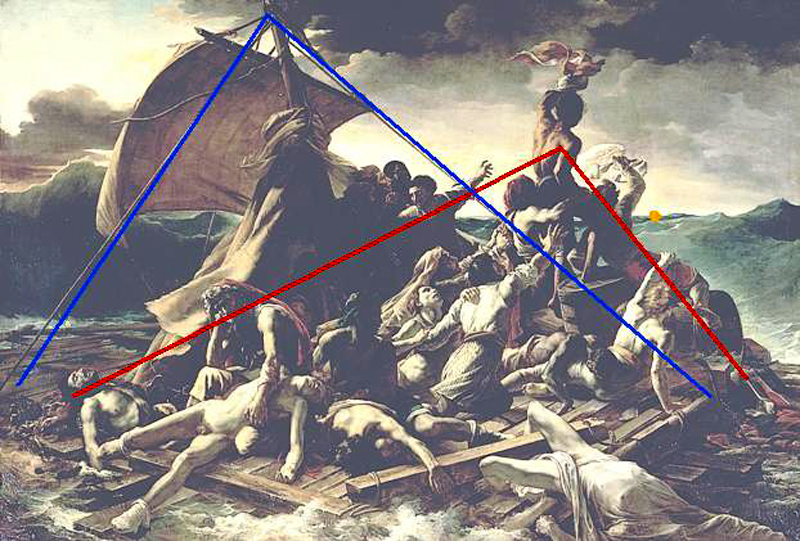

The 27-year-old Géricault found it a fascinating story and wanted to immortalize it. The result made him world famous. In keeping with 19th-century Romanticism, Géricault decided on a large canvas depicting a less horrific but emotionally poignant event: the first sighting of the Argus. The work gives shape to hope, to freedom within reach, and at the same time to an illusion, but only the knowledgeable viewer is aware of this.

♦ Description of the work

The painting itself shows a palette of emotions: from despair to false hope. The ship itself is barely visible, but the emotions are all the more so. Some have already given up hope and sink back into their stupor. That ebb and flow, that movement of moods, is rendered with precision. Everything has been studied and carefully thought out by Géricault, who in the fall of 1818 was able to transfer the entire composition onto the 5 by 7.5 meter canvas.

Central to the story is the tiny dot in the distance that shows the barely visible sail of the rescue ship. But the viewer first notices the high waves and cloudy sky surrounding the raft. Then he sees the passengers gesturing for attention, pointing to the ship and at the same time involving the viewer. The hostile nature and the dead surrounding the people on board make the whole scene sensational.

Géricault and this work are characterized by razor-sharp realism and the ambition to create heroic and monumental works. He worked with live models and, as much as possible, preliminary studies of corpses, severed heads, and amputated limbs. Although his painting borders on the perverse and morbid fantasy, it remains essentially a realistically painted indictment.

♦ Meaning

On August 25, 1819, The Raft was presented under the title Shipwreck at the Salon (the 19th-century exhibition of visual arts in Paris that was organized annually under state control).

In some circles, the work provoked resistance. It was seen as a political indictment of the incompetence of the royalist captain of the Medusa. People were also disturbed by the black figure on the raft and suspected a veiled indictment of slavery. In short, the political significance of the painting overshadowed its artistic value.

Géricault was disappointed and discouraged (whether rightly or wrongly). Exhausted and ill (both physically and emotionally), he traveled to London, where he arrived in 1820 with his “Raft.”

He welcomed more than 50,000 paying visitors. Whether it was considered an indictment or disaster tourism, it proved to be a success nonetheless.

The painting also has a deeper meaning. It refers to the changing role or status of the artist after the Ancien Régime, when traditional patrons such as the nobility, clergy, and bourgeoisie disappeared and artists no longer painted on commission but had to come up with their own commissions. The artist finds himself, as it were, on the raft, without any binding guidelines (style or subject), drifting aimlessly on the waves, confronted with total freedom.

Around 1880, this led to the emergence of various movements such as Impressionism, Expressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, etc., and art began to reflect the artist's inner spiritual struggle.

♦ Trivia

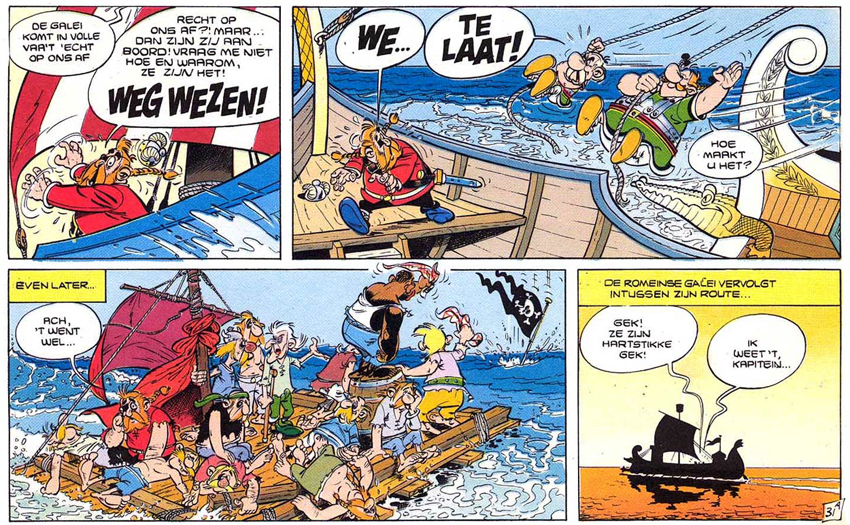

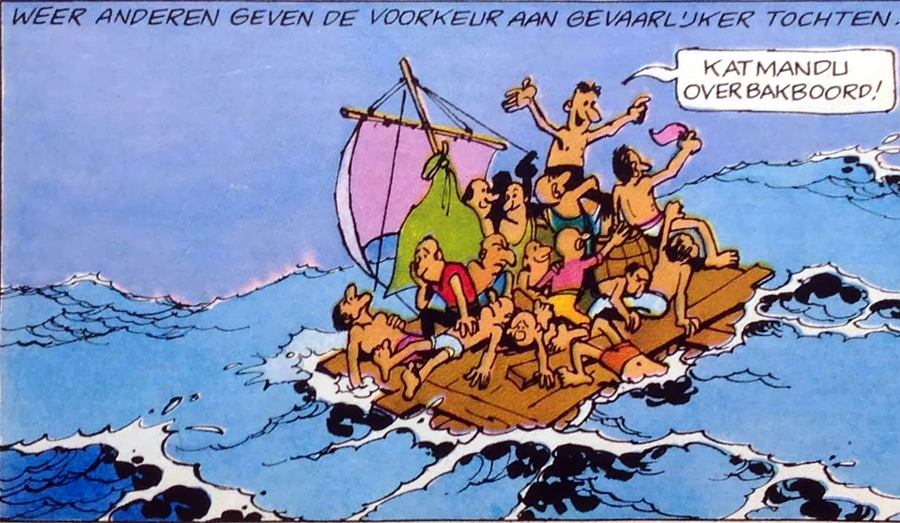

A nice illustration of the painting's popularity can be found in the well-known comic book Asterix the Legionary (English: Asterix and the First Legion, 1967), in which the painting is parodied: after a swift sea battle with the main characters, all that remains of a pirate ship is a raft with battered passengers, which bears a striking resemblance to Géricault's painting.

A bewildered shipwreck survivor sighs: “Je suis médusé!” (“I am amazed”). Whereas the Dutch translator did not understand this pun or did not know how to translate it with a joke, the exclamation in Derek Hockridge's English translation is “We've been framed, by Jericho!”, which of course must be read in its second meaning as “We have been framed by Géricault”.

Source: Historia

Géricault, Théodore_Medusas raft

References

Historia

2 mrt 2013

Photos

Wikipedia

Art lijst

Schilderijen

- Bosch, Hieronymus – The Peddler

- Bosch, Hieronymus_The Haywain triptych

- Botticelli, Sandro_Primavera / Spring

- Brueghel the Elder, Pieter – The Tower of Babel

- Campin, Robert — Mérode Triptych

- Courbet, Gustave_The painters Studio

- Dali, Salvadore_The Temptation of Saint Anthony

- Dou, Gerard_the Quack Doctor

- Eyck van Barthélemy_Still life with books

- Fra Angelico_Annunciation

- Géricault, Théodore_Medusas raft

- Magritte, Rene_Prohibited to depict

- Matsys, Quinten_The money changer and his wife

- Memling, Hans_Two horses in a landscape

- Picasso, Pablo_Guernica

- Rembrandt_Abraham en de drie engelen

- Rembrandt_Elsje Christiaens

- Unknown – 16th century: Four depictions of a physician

- Velazquez, Diego_Las Meninas

Schilderijen en de dokter

- Agenesia Sacrale (a rare congenital disorder in which the fetal development of the lower spine)

- Alopecia areata (hair loss)

- Arthrogryposis congenita (birth defect, joints contracted)

- Artritis psoriatica (inflammatory disease of the joint)

- Artritis reumatoïde

- Breast development (delayed)

- Bubonic plague

- Diphtheria

- Eye surgery

- Flat foot and Pointed Foot

- Gigantism and Acromegaly

- Goiter (struma)

- Hare lip (cheiloschisis) / cleft palate

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Hunger edema

- Influenza Epidemic of 1858

- Insanity - Malle Babbe (1640)

- Leprosy

- Lovesick, pregnancy

- Lymph node tumor (lymphoma), non-Hodgkin

- Manic Depression Psychosis

- Measles / Rubella? (acute viral infection)

- Melanoma or nevus (birthmark)

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Murder (pneumothorax, arterial bleeding)

- Neurofibromatosis

- Osteoarthritis / hallux valgus

- Osteomyelitis

- Otitis media (acute middle ear infection)

- Parotitis (mumps)

- Polio

- Prepatellar bursitis

- Progeria

- Pseudohermafroditism

- Pseudozwangerschap

- Psychoneurose (acute)

- Rachitische borst

- Reumatische koorts (acute)

- Rhinophyma of knobbelneus

- Rhinophyma rosacea_depressie

- Rhinoscleroma

- Schimmelziekte_Favus

- Syfilis (harde 'sjanker')

- Tandcariërs

- The Extraction of the Stone of Madness

- Tuberculose long

- Ziekte van Paget

Schilders

Historie lijst

- 1632-1723_Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

- 1749-1823_Edward Jenner

- 1818-1865_Ignaz Semmelweis

- 1822-1895_Louis Pasteur

Wetenswaardigheden lijst

- 1887 Psychiatric Hospital

- Animals on duty

- Bizarre advice for parents

- Bloodletting

- Bloodthirsty Hungarian Countess Elizabeth Báthory (1560–1614)

- Butler escaped punishment three times.

- Dance mania / Saint Vitus Dance

- Doctors’ advice did more harm than good

- French Revolution Louis XVI

- Frontal syndrome (Phineas Gage)

- Heart disease (Egyptian princess)

- Ice Age (minor)_1300-1850

- Ivan IV de Verschrikkelijke (1530-1584)

- Kindermishandeling

- Koketteren met koningin Victoria

- Koningin door huidcrème vergiftigd

- Kraambedpsychose (Margery Kempe)

- Massacre in Beirut

- ME stonden bol van de seks

- Mummie bij de dokter

- Plee, Gemak of Kakstoel

- Prostaatkanker (mummie)

- Sexhandel in Londen

- Swaddling baby

- Syfilis was in de mode

- Testikels opofferen

- Tropische ziekten werden veroveraars fataal

- Vrouwen als beul in WOII

- Wie mooi wil zijn moet pijn lijden

- Zonnekoning woonde in een zwijnenstal