♦ What is whooping cough?

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable bacterial disease.

Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or three months of severe coughing fits.

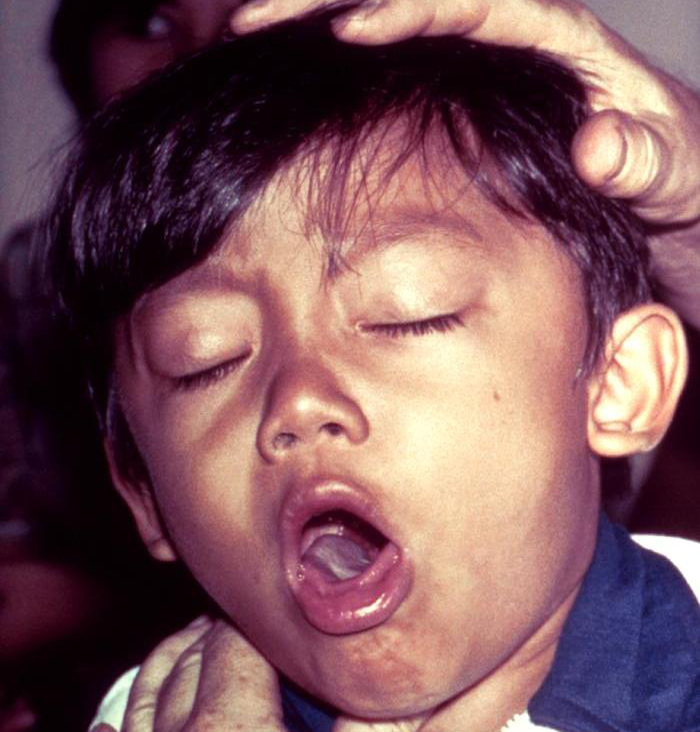

Following a fit of coughing, a high-pitched whoop sound or gasp may occur as the person breathes in.

The violent coughing may last for 10 or more weeks, hence the phrase "100-day cough".

The cough may be so hard that it causes vomiting, rib fractures, and fatigue.

Children less than one year old may have little or no cough and instead have periods where they cannot breathe.

♦ Infectious

People are infectious from the start of symptoms until about three weeks into the coughing fits.

Those treated with antibiotics are no longer infectious after five days.

♦ Signs and symptoms

The classic symptoms of pertussis are a paroxysmal cough, inspiratory whoop, and fainting, or vomiting after coughing.

The cough from pertussis has been documented to cause subconjunctival hemorrhages, rib fractures, urinary incontinence, hernias, and vertebral artery dissection.

Violent coughing can cause the pleura to rupture, leading to a pneumothorax.

Vomiting after a coughing spell or an inspiratory whooping sound on coughing almost doubles the likelihood that the illness is pertussis.

The absence of a paroxysmal cough or posttussive emesis, though, makes it almost half as likely.

Classic Whooping Cough is divided into 3 successive stages:

- catarrhal stage

The illness usually starts with mild respiratory symptoms include mild coughing, sneezing, or a runny nose (known as the catarrhal stage).

- paroxysmal stage

After one or two weeks, the coughing classically develops into uncontrollable fits, sometimes followed by a high-pitched "whoop" sound, as the person tries to inhale.

About 50% of children and adults "whoop" at some point in diagnosed pertussis cases during the paroxysmal stage.

This stage usually lasts two to eight weeks, or sometimes longer.

- convalescent stage

A gradual transition then occurs to the convalescent stage, which usually lasts one to four weeks.

This stage is marked by a decrease in paroxysms of coughing, although paroxysms may occur with subsequent respiratory infection for many months after the onset of pertussis.

Symptoms of pertussis can be variable, especially between immunized and non-immunized people.

Those that are immunized can present with a more mild infection; they may only have the paroxysmal cough for a couple of weeks, and it may lack the "whooping" characteristic.

Although immunized people have a milder form of the infection, they can spread the disease to others who are not immune.

♦ Incubation period

The time between exposure and the development of symptoms is on average 7–14 days (range 6–20 days), rarely as long as 42 days.

Disease may occur in those who have been vaccinated, but symptoms are typically milder.

♦ Cause

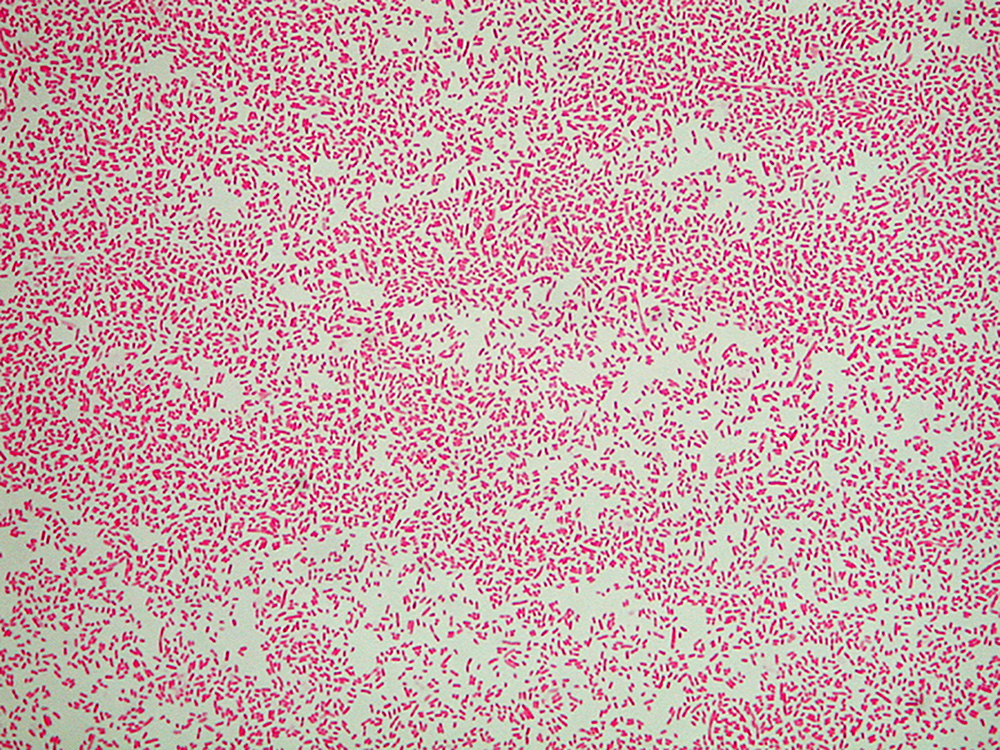

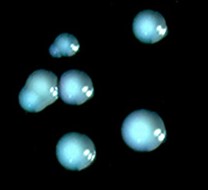

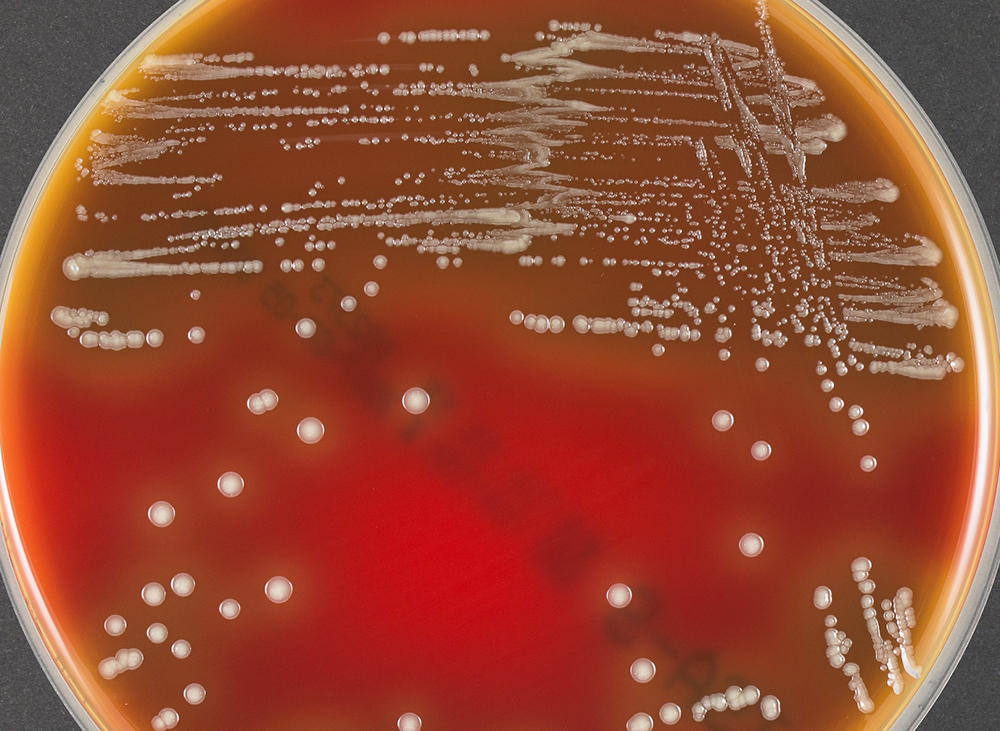

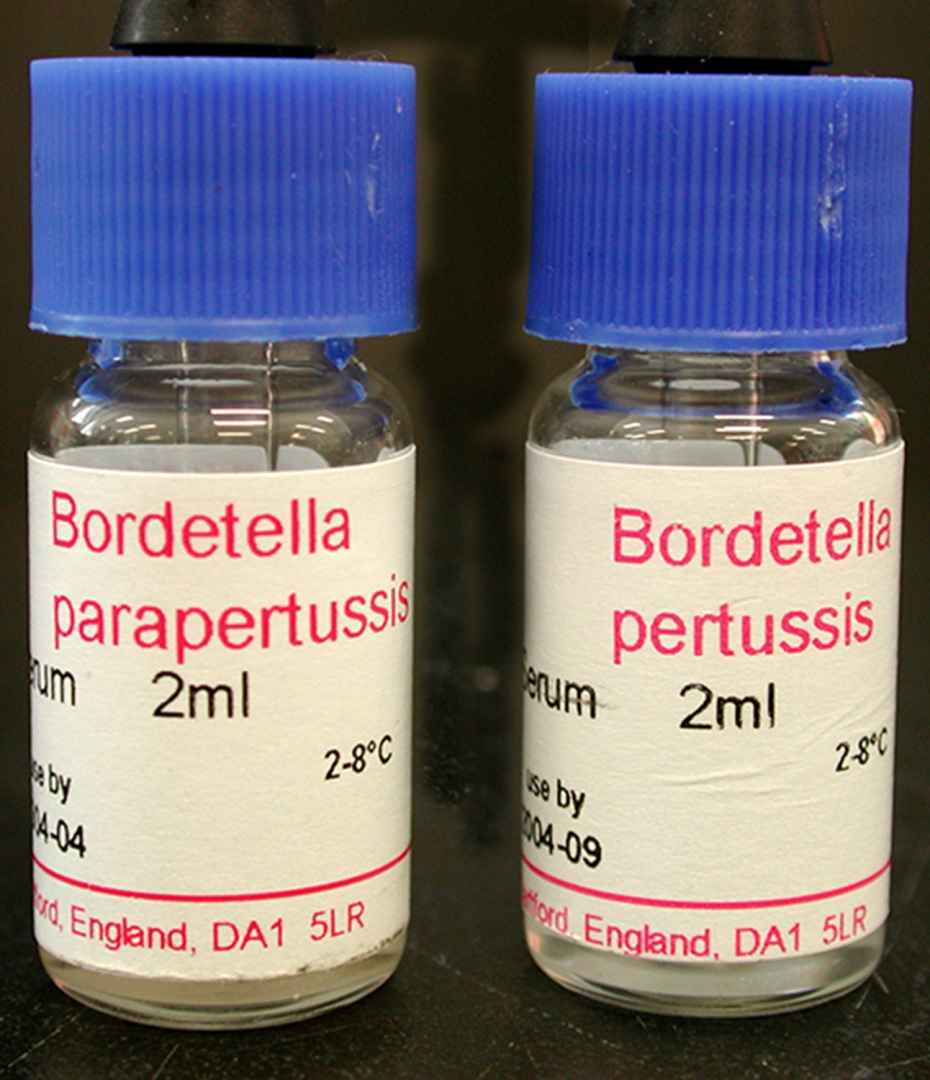

Pertussis is caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis.

It is an airborne disease (through droplets) that spreads easily through the coughs and sneezes of an infected person.

♦ Mechanism

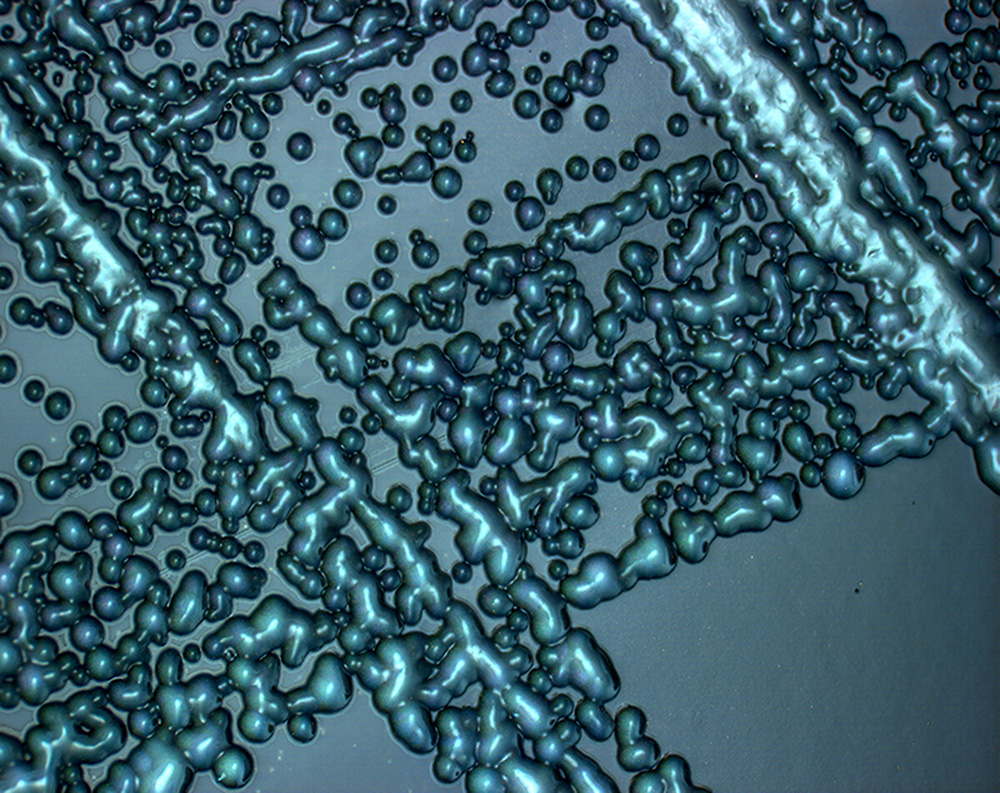

After the bacteria are inhaled, they initially adhere to the ciliated epithelium in the nasopharynx.

Surface proteins of B. pertussis, including filamentous hemaglutinin and pertactin, mediate attachment to the epithelium. The bacteria then multiply.

In infants, who experience more severe disease, the bacteria spread down to the lungs.

The bacteria secretes a number of toxins. Tracheal cytotoxin (TCT), a fragment of peptidoglycan, kills ciliated epithelial cells and thereby inhibits the mucociliary elevator by which mucus and debris are removed.

TCT may contribute to the cough characteristic of pertussis.

The cough may also be caused by a yet-to-be identified "cough toxin".

Pertussis toxin causes lymphocytosis by an unknown mechanism.

The elevated number of white blood cells leads to pulmonary hypertension, a major cause of death by pertussis.

In infants who develop encephalopathy, cerebral hemorrhage and cortical atrophy occur, likely due to hypoxia.

♦ Diagnosis

- Based on symptoms

A physician's overall impression is most effective in initially making the diagnosis.

Single factors are much less useful.

In adults with a cough of less than 8 weeks, vomiting after coughing or a "whoop" is supportive.

If there are no bouts of coughing or there is a fever the diagnosis is unlikely.

In children who have a cough of less than 4 weeks vomiting after coughing is somewhat supportive but not definitive.

- Lab tests

Methods used in laboratory diagnosis include

- culturing of nasopharyngeal swabs on a nutrient medium (Bordet–Gengou medium),

- polymerase chain reaction (PCR),

- direct fluorescent antibody (DFA), and

- serological methods (e.g. complement fixation test).

The bacteria can be recovered from the person only during the first three weeks of illness, rendering culturing and DFA useless after this period, although PCR may have some limited usefulness for an additional three weeks.

Serology may be used for adults and adolescents who have already been infected for several weeks to determine whether antibody against pertussis toxin or another virulence factor of B. pertussis is present at high levels in the blood of the person.

♦ Differential diagnosis

A similar, milder disease is caused by B. parapertussis.

♦ Prevention

Prevention is mainly by vaccination with the pertussis vaccine.

Initial immunization is recommended between six and eight weeks of age, with four doses to be given in the first two years of life.

Protection from pertussis decreases over time, so additional doses of vaccine are often recommended for older children and adults.

♦ Vaccine

Pertussis vaccines are effective at preventing illness and are recommended for routine use by the World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine saved an estimated half a million lives in 2002.

The multicomponent acellular pertussis vaccine is 71–85% effective, with greater effectiveness against more severe strains.

However, despite widespread vaccination, pertussis has persisted in vaccinated populations and is today "one of the most common vaccine-preventable diseases in Western countries".

The 21st-century resurgences in pertussis infections is attributed to a combination of waning immunity and bacterial mutations that elude vaccines.

Immunization does not confer lifelong immunity; a 2011 CDC study indicated that protection may only last three to six years. This covers childhood, which is the time of greatest exposure and greatest risk of death from pertussis.

♦ Vaccination (pregnancy)

Vaccination during pregnancy is highly effective at protecting the infant from pertussis during their vulnerable early months of life, and is recommended in many countries.

♦ Treatment

Antibiotics may be used to prevent the disease in those who have been exposed and are at risk of severe disease.

In those with the disease, antibiotics are useful if started within three weeks of the initial symptoms, but otherwise have little effect in most people.

In pregnant women and children less than one year old, antibiotics are recommended within six weeks of symptom onset.

Antibiotics used include erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin, or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

The antibiotics erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin are typically the recommended treatment.

Newer macrolides are frequently recommended due to lower rates of side effects.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) may be used in those with allergies to first-line agents or in infants who have a risk of pyloric stenosis from macrolides.

A reasonable guideline is to treat people

age >1 year within 3 weeks of cough onset and infants

age <1 year and pregnant women within 6 weeks of cough onset.

If the person is diagnosed late, antibiotics will not alter the course of the illness, and even without antibiotics, they should no longer be spreading pertussis.

When used early, antibiotics decrease the duration of infectiousness, and thus prevent spread.

Short-term antibiotics (azithromycin for 3–5 days) are as effective as long-term treatment (erythromycin 10–14 days) in eliminating B. pertussis with fewer and less severe side effects.

People with pertussis are most infectious during the first two weeks following the onset of symptoms. Effective treatments of the cough associated with this condition have not been developed.[57] The use of over the counter cough medications is discouraged and has not been found helpful.

♦ Prognosis

While most healthy older children and adults fully recover, infection in newborns is particularly severe.

Pertussis is fatal in an estimated 0.5% of US infants under one year of age.

First-year infants are also more likely to develop complications, such as: apneas (31%), pneumonia (12%), seizures (0.6%) and encephalopathy (0.15%).

This may be due to the ability of the bacterium to suppress the immune system.

♦ Epidemiology

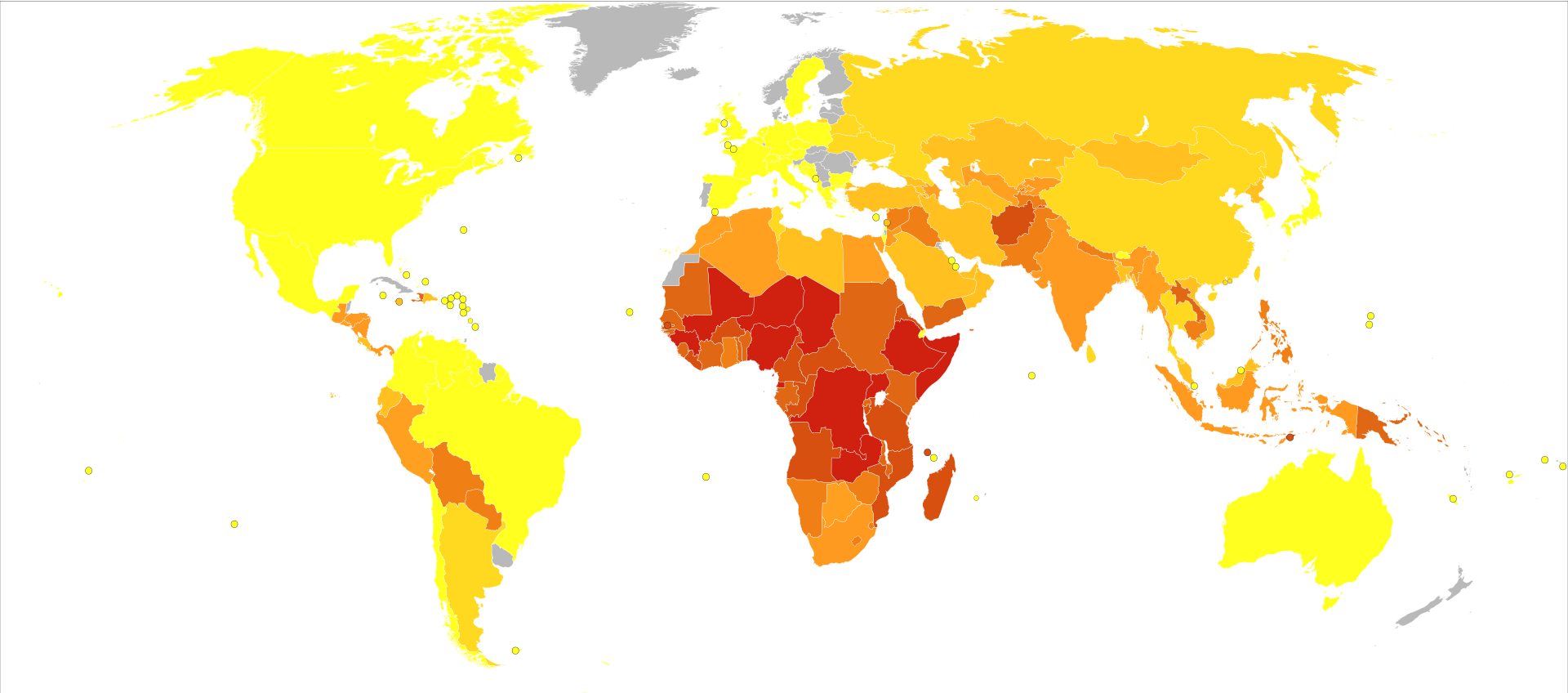

Worldwide, whooping cough affects around 16 million people yearly.

One estimate for 2013 stated it resulted in about 61,000 deaths – down from 138,000 deaths in 1990.

Another estimated 195,000 child deaths yearly from the disease worldwide.

This is despite generally high coverage with the DTP and DTaP vaccines. Pertussis is one of the leading causes of vaccine-preventable deaths worldwide.

About 90% of all cases occur in developing countries.

Whooping Cough

Related

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whooping_cough Photos

wikipedia

https://www.museumofhealthcare.ca/explore/exhibits/vaccinations/pertussis.html

MMIZ, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam_Loes van damme

- Actinomycosis

- Anthrax

- Biopsy Sinusitis_Aspergillus flavus

- Botulism

- Brucellosis

- Cat Scratch Disease

- Cellulitis

- Cholera

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Cystic Fibrosis_CF

- Diphtheria

- Erysipelas

- Erysipeloid or fish poison

- Legionnaires disease

- Lemierre syndrome

- Leprosy

- Listeriosis

- Lyme / Borreliosis

- Melioidosis

- Meningitis

- Plague

- Syphilis

- Tetanus

- Trench Mouth_Plaut-Vincent_acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Tularemia_Rabbit Fever

- Typhoid fever (Epidemic typhus)

- Whooping Cough