♦ What is Lyme disease (borreliosis)?

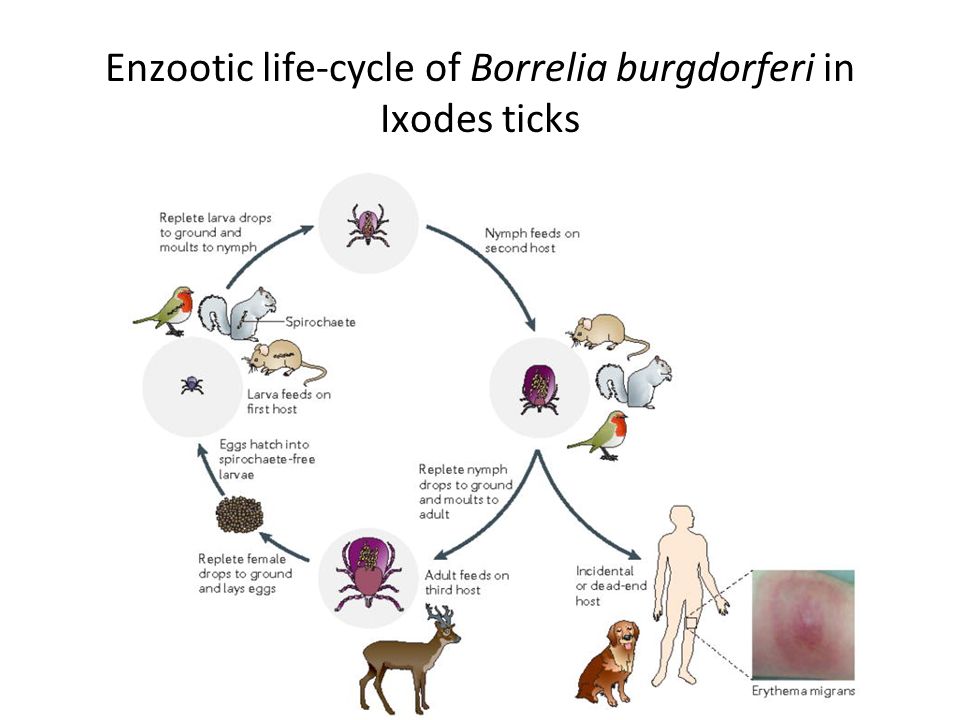

Also known as Lyme borreliosis, is an infectious disease caused by a bacteria named Borrelia spread by ticks.

The most common sign of infection is an expanding area of redness on the skin, known as erythema migrans, that appears at the site of the tick bite about a week after it occurred. The rash is typically neither itchy nor painful. Approximately 70-80% of infected people develop a rash.

Other early symptoms may include fever, headache and tiredness. If untreated, symptoms may include loss of the ability to move one or both sides of the face, joint pains, severe headaches with neck stiffness, or heart palpitations, among others.

Months to years later, repeated episodes of joint pain and swelling may occur. Occasionally, people develop shooting pains or tingling in their arms and legs. Despite appropriate treatment, about 10 to 20% of people develop joint pains, memory problems, and tiredness for at least six months.

Lyme disease is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected ticks of the genus Ixodes.

The disease does not appear to be transmissible between people, by other animals, or through food.

Diagnosis is based upon a combination of symptoms, history of tick exposure, and possibly testing for specific antibodies in the blood. Blood tests are often negative in the early stages of the disease.

Testing of individual ticks is not typically useful.

Prevention includes efforts to prevent tick bites such as by wearing clothing to cover the arms and legs, and using DEET-based insect repellents. Using pesticides to reduce tick numbers may also be effective. Ticks can be removed using tweezers. If the removed tick was full of blood, a single dose of doxycycline may be used to prevent development of infection, but is not generally recommended since development of infection is rare.

If an infection develops, a number of antibiotics are effective, including doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime. Standard treatment usually lasts for two or three weeks. Some people develop a fever and muscle and joint pains from treatment which may last for one or two days. In those who develop persistent symptoms, long-term antibiotic therapy has not been found to be useful. ♦ Signs and Symptoms

Lyme disease can affect multiple body systems and produce a broad range of symptoms. Not all patients with Lyme disease have all symptoms, and many of the symptoms are not specific to Lyme disease, but can occur with other diseases, as well. The incubation period from infection to the onset of symptoms is usually one to two weeks, but can be much shorter (days), or much longer (months to years). Symptoms most often occur from May to September, because the nymphal stage of the tick is responsible for most cases. Asymptomatic infection exists, but occurs in less than 7% of infected individuals in the United States. Asymptomatic infection may be much more common among those infected in Europe.

• early localized infections

Early localized infection can occur when the infection has not yet spread throughout the body. Only the site where the infection has first come into contact with the skin is affected. The classic sign of early local infection with Lyme disease is a circular, outwardly expanding rash called erythema migrans (EM), which occurs at the site of the tick bite three to 32 days after the tick bite. The rash is red, and may be warm, but is generally painless. Classically, the innermost portion remains dark red and becomes indurated (thicker and firmer), the outer edge remains red, and the portion in between clears, giving the appearance of a bull's eye, known as a target lesion. However, partial clearing is uncommon, and the bull's-eye pattern more often involves central redness.

• early disseminated infections

Within days to weeks after the onset of local infection, the Borrelia bacteria may begin to spread through the bloodstream. Various acute neurological problems, termed neuroborreliosis, appear in 10–15% of untreated people. These include facial palsy, which is the loss of muscle tone on one or both sides of the face, as well as meningitis, which involves severe headaches, neck stiffness, and sensitivity to light. Inflammation of the spinal cord's nerve roots can cause shooting pains that may interfere with sleep, as well as abnormal skin sensations. Mild encephalitis may lead to memory loss, sleep disturbances, or mood changes. In addition, some case reports have described altered mental status as the only symptom seen in a few cases of early neuroborreliosis. The disease may adversely impact the heart's electrical conduction system and can cause abnormal heart rhythms such as atrioventricular block.

• late disseminated infection

After several months, untreated or inadequately treated people may go on to develop severe and chronic symptoms that affect many parts of the body, including the brain, nerves, eyes, joints, and heart. Many disabling symptoms can occur, including permanent impairment of motor or sensory function of the lower extremities in extreme cases.

The late disseminated stage is where the infection has fully spread throughout the body. Chronic neurologic symptoms occur in up to 5% of untreated people. A polyneuropathy that involves shooting pains, numbness, and tingling in the hands or feet may develop. A neurologic syndrome called Lyme encephalopathy is associated with subtle cognitive difficulties, insomnia, a general sense of feeling unwell, and changes in personality. Other problems, however, such as depression and fibromyalgia, are no more common in people with Lyme disease than in the general population.

A number of studies have found the causative agent of Lyme Borrelia burgdorferi in both the meninges and brains of people with neurological symptoms. Lyme arthritis usually affects the knees. In a minority of people, arthritis can occur in other joints, including the ankles, elbows, wrists, hips, and shoulders. Pain is often mild or moderate, usually with swelling at the involved joint.

♦ Cause

Is caused by spirochetal bacteria from the genus Borrelia, which has 52 known species. Three main species (Borrelia garinii, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia burgdorferi s.s.) are the main causative agents of the disease in humans, while a number of others have been implicated as possibly pathogenic. Borrelia species in the species complex known to cause Lyme disease are collectively called Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato

Borrelia are microaerophilic and slow-growing—the primary reason for the long delays when diagnosing Lyme disease and have been found to have greater strain diversity than previously estimated. The strains differ in clinical symptoms and/or presentation as well as geographic distribution.

Except for Borrelia recurrentis (which causes louse-borne relapsing fever and is transmitted by the human body louse), all known species are believed to be transmitted by ticks.

♦ Diagnosis

Lyme disease is diagnosed clinically based on symptoms, objective physical findings (such as EM, facial palsy, or arthritis), or a history of possible exposure to infected ticks, as well as serological blood tests. The EM rash is not always a bull's eye, i.e., it can be solid red. When making a diagnosis of Lyme disease, health care providers should consider other diseases that may cause similar illnesses. Not all individuals infected with Lyme disease develop the characteristic bull's-eye rash, and many may not recall a tick bite.

Because of the difficulty in culturing Borrelia bacteria in the laboratory, diagnosis of Lyme disease is typically based on the clinical exam findings and a history of exposure to endemic Lyme areas. The EM rash, which does not occur in all cases, is considered sufficient to establish a diagnosis of Lyme disease even when serologic blood tests are negative. Serological testing can be used to support a clinically suspected case, but is not diagnostic by itself. Diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease is often complicated by a multifaceted appearance and nonspecific symptoms, prompting one reviewer to call Lyme the new "great imitator".

Lyme disease may be misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, lupus, Crohn's disease, HIV, or other autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases. As all people with later-stage infection will have a positive antibody test, simple blood tests can exclude Lyme disease as a possible cause of a person's symptoms.

• laboratory testing

Several forms of laboratory testing for Lyme disease are available, some of which have not been adequately validated. The most widely used tests are serologies, which measure levels of specific antibodies in a patient's blood.

These tests may be negative in early infection as the body may not have produced a significant quantity of antibodies, but they are considered a reliable aid in the diagnosis of later stages of Lyme disease.

Serologic tests for Lyme disease are of limited use in people lacking objective signs of Lyme disease because of false positive results and cost.

The serological laboratory tests most widely available and employed are the Western blot and ELISA.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for Lyme disease have also been developed to detect the genetic material (DNA) of the Lyme disease spirochete. PCR tests are susceptible to false positive results from poor laboratory technique. Even when properly performed, PCR often shows false negative results with blood and cerebrospinal fluid specimens

♦ Prevention

Protective clothing includes a hat, long-sleeved shirt, and long pants tucked into socks or boots. Light-colored clothing makes the tick more easily visible before it attaches itself. People should use special care in handling and allowing outdoor pets inside homes because they can bring ticks into the house. People who work in areas with woods, bushes, leaf litter, and tall grass are at risk of becoming infected with Lyme at work.

• tick removal

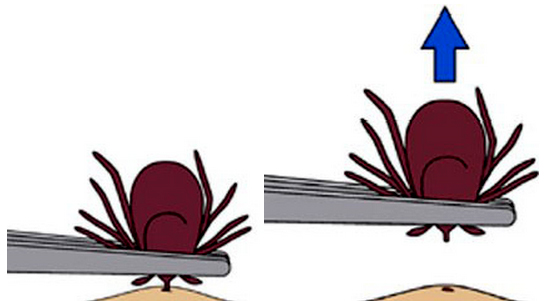

Attached ticks should be removed promptly, as removal within 36 hours can reduce transmission rates.

The best method is simply to pull the tick out with tweezers as close to the skin as possible, without twisting, and avoiding crushing the body of the tick or removing the head from the tick's body. The risk of infection increases with the time the tick is attached, and if a tick is attached for less than 24 hours, infection is unlikely. However, since these ticks are very small, especially in the nymph stage, prompt detection is quite difficult. ♦ Treatment

Antibiotics are the primary treatment. The specific approach to their use is dependent on the individual affected and the stage of the disease. For most people with early localized infection, oral administration of doxycycline is widely recommended as the first choice, as it is effective against not only Borrelia bacteria but also a variety of other illnesses carried by ticks. Doxycycline is contraindicated in children younger than eight years of age and women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, alternatives to doxycycline are amoxicillin, cefuroxime axetil, and azithromycin. Individuals with early disseminated or late infection may have symptomatic cardiac disease, refractory Lyme arthritis, or neurologic symptoms like meningitis or encephalitis.

These treatment regimens last from one to four weeks. If joint swelling persists or returns, a second round of antibiotics may be considered. Outside of that, a prolonged antibiotic regimen lasting more than 28 days is not recommended as no clinical evidence shows it to be effective.

♦ Prognosis

For early cases, prompt treatment is usually curative. However, the severity and treatment of Lyme disease may be complicated due to late diagnosis, failure of antibiotic treatment, and simultaneous infection with other tick-borne diseases (coinfections), including ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, and immune suppression in the patient.

It is believed that less than 5% of people have lingering symptoms of fatigue, pain, or joint and muscle aches at the time they finish treatment. These symptoms can last for more than 6 months. This condition is called post-treatment lyme disease syndrome

Lyme / Borreliosis

Related

- Actinomycosis

- Anthrax

- Biopsy Sinusitis_Aspergillus flavus

- Botulism

- Brucellosis

- Cat Scratch Disease

- Cellulitis

- Cholera

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Cystic Fibrosis_CF

- Diphtheria

- Erysipelas

- Erysipeloid or fish poison

- Legionnaires disease

- Lemierre syndrome

- Leprosy

- Listeriosis

- Lyme / Borreliosis

- Melioidosis

- Meningitis

- Plague

- Syphilis

- Tetanus

- Trench Mouth_Plaut-Vincent_acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Tularemia_Rabbit Fever

- Typhoid fever (Epidemic typhus)

- Whooping Cough